April 8, 2022

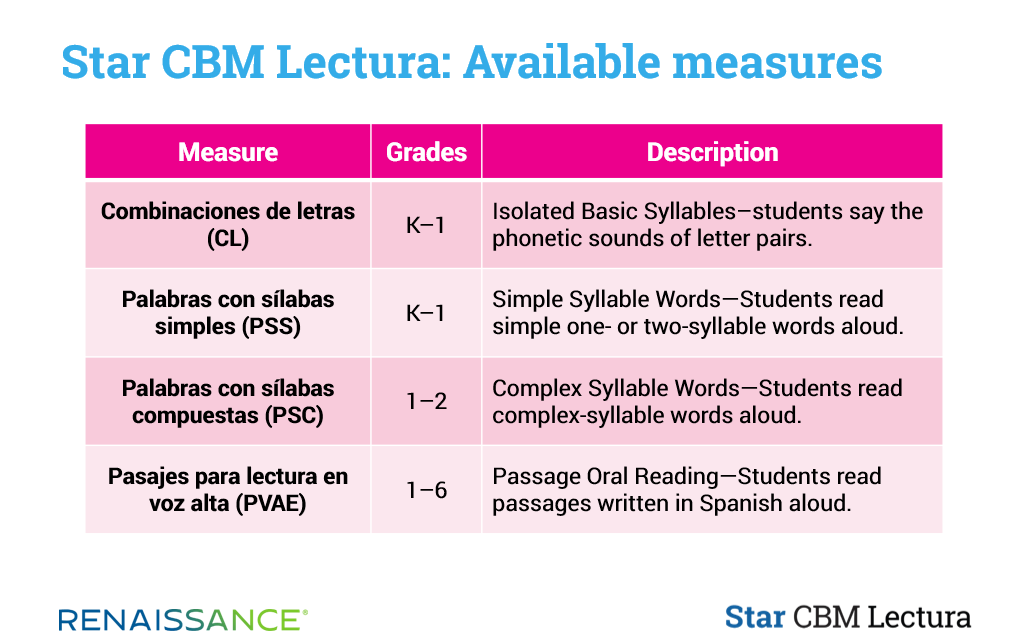

In 2020, Renaissance introduced Star CBM Reading, which assesses K–6 students’ literacy development in English. For Back-to-School 2022, we’re releasing the new Star CBM Lectura to assess K–6 students’ literacy development in Spanish as well.

We recently had the opportunity to discuss Star CBM Lectura—including the research and best practices that informed its design—with four of our Renaissance colleagues: Doris Chávez-Linville, Director of Linguistic and Culturally Diverse Innovation; Dr. Scott McConnell, Director of Assessment Innovation; Heidi Lund, Senior Product Manager; and Amy Patnoe, Project Manager.

Highlights from our conversation appear below.

Why did Renaissance create Star CBM Lectura? How does it differ from other Spanish assessments?

Heidi Lund: After we released Star CBM Reading, our school and district partners began asking us for a Spanish CBM as well. These requests aligned perfectly with our commitment to biliteracy development, so we were eager to respond.

Unfortunately, this was in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when no one knew where students would be learning or what the typical school day would look like. We wanted to “do this right” with careful design of the new Spanish measures and robust field testing, but the uncertainties of the 2020–2021 school year made planning difficult.

By spring 2021, however, we’d reached a critical mass in the number of districts volunteering to participate in the field testing. At that point, it made sense to bring together our internal teams and external advisors to begin the design process. Input from educators played a key role here, with teachers telling us how existing Spanish CBMs were failing to meet their needs. They wanted a measure that deeply reflected students’ language and literacy development in Spanish.

Over the last few years, we’ve invested heavily in our computer-adaptive Star Assessments in Spanish, and Star CBM Lectura builds on this commitment. We want to provide educators with a Spanish assessment that they can administer to students one-on-one, along with the flexibility and differentiated data that’s provided by curriculum-based measurement. Educators understand that CATs and CBMs have unique strengths. Together, they provide detailed information about what to do next in the classroom.

Doris Chávez-Linville: Our mission at Renaissance is to accelerate learning for all. We recognize that this is a big mission—and something that is an ongoing process that we are always working toward. We also recognize that equity does not mean “the same.” Too often, testing companies have said something like, “We have a CBM in English, so let’s translate it into Spanish!” This is clearly not the way to achieve equity in education.

From the beginning, we knew that we needed to fully understand the research on bilingualism and biliteracy and to work with experts in the field. We also asked educators, When you’re assessing students who are learning to read in both languages, what does that look like? And we used this input to design authentic Spanish measures, rather than translating or transadapting existing English measures. As Heidi said, our focus remained firmly on the teachers and the students.

What design best practices did we follow when creating Star CBM Lectura? What makes the measures authentic?

Scott McConnell: When we created Star CBM Reading, one of our guiding principles was simplicity. Rather than developing every measure under the sun, we followed the research and focused on foundations of literacy that are most predictive of learning to read in English: Letter Sounds, Phoneme Segmentation, Nonsense Word Reading, and Passage Oral Reading. Simplicity meant sticking to the major pillars to provide great measures of progress—and empowering teachers to intervene for those students needing supplemental instruction.

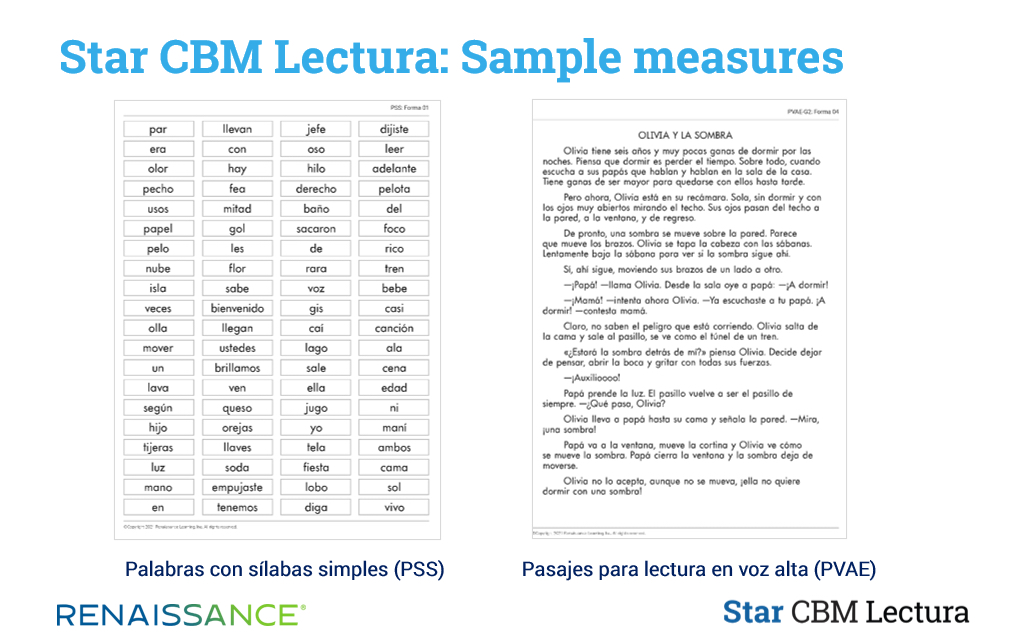

We took the same approach with Star CBM Lectura, while also acknowledging that learning to read in Spanish has differences from learning to read in English. This is why, for example, Star CBM Lectura doesn’t include measures for Letter Naming, even though other CBMs in Spanish do. So why don’t we? Because our goal is to create an authentic assessment, as Doris explained. Reviewing the research and consulting with experts led us to focus on very young students reading simple and then more complex syllables, which is typically the first instructional and developmental component of Spanish literacy.

To put this another way, “parity” with our English CBM doesn’t depend on what the measures look like. Instead, it’s rooted in our commitment to empowering teachers and strengthening the connection between assessment and classroom instruction.

Doris Chávez-Linville: When I first came to the US from Mexico, I was always surprised when people would ask how to spell my name. In Spanish, there’s only one way to spell “Doris.” This is because Spanish is a transparent language, with a one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds. Unlike English, Spanish does not have short and long vowels or hard and soft consonants. In Spanish, children begin not by learning the letter names but by learning sounds and then syllables. For example, a child learning to spell the word murciélago would break it down into syllables rather than individual letters: mur-cié-la-go.

Dr. Jose Medina jokingly uses the phrase “Spanish á la anglais” to refer to programs that have obviously been translated from English. When teachers who work in bilingual education see a Letter Naming measure in Spanish, their immediate reaction is: It’s been translated. In Spanish, letter names and the order of the alphabet are typically taught in grade 2—as part of dictionary skills or sorting skills, not literacy skills.

Amy Patnoe: Before I joined Renaissance, I managed bilingual programming in a public school district. When we implemented a CBM in Spanish, we were expected to implement the same measures that our English CBM provided. Bilingual educators immediately contacted me with concerns. As Doris and Scott have explained, foundational literacy development differs between Spanish and English. There was immense frustration that the CBM our district implemented in Spanish did not honor these differences and—therefore—did not honor our students’ needs.

Teachers quickly noticed that the Letter Naming measure in Spanish was not indicative of the reading progress students were making, particularly in the early grades. Teachers saw that their CBM data was not triangulating with other assessments they were using in the classroom, and they had a challenging time narrating the rationale behind these differences.

I began working with the district’s Accountability, Reliability, and Evaluation department to adjust the measure. This created further psychometric challenges because we were then straying from the way the assessment was supposed to be implemented. If we’d had a CBM that was authentically designed in Spanish, these issues would not have arisen, and we would have been able to invest our advocacy efforts for Emergent Bilingual students in other ways.

What does the Star CBM Lectura field test involve? What feedback have we received from educators and students?

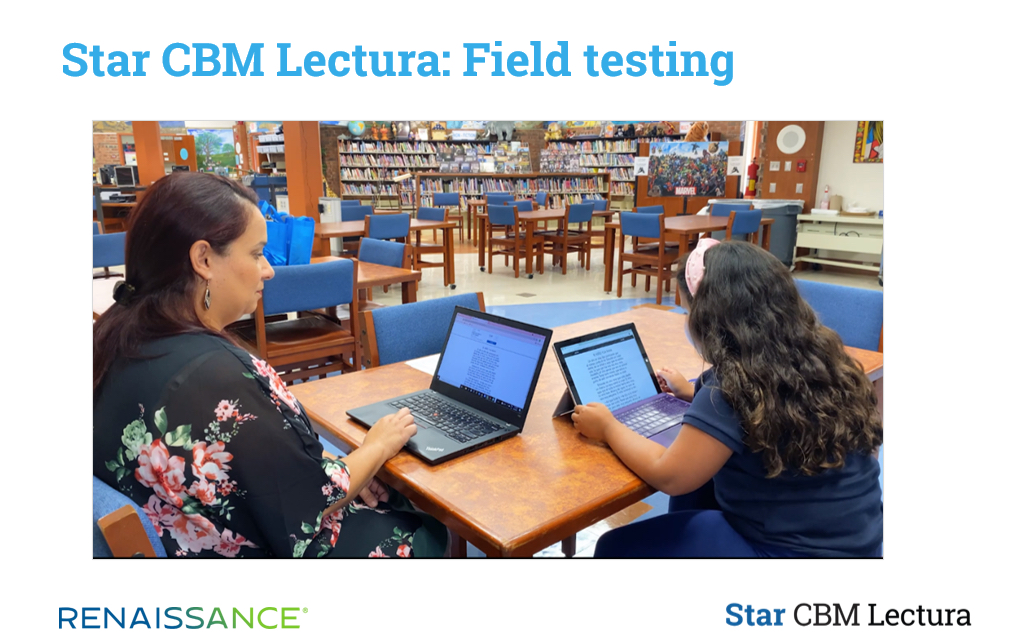

Heidi Lund: Thousands of students are participating in the field testing, which we designed to be as efficient as possible, knowing that educators have more demands than ever on their time this year. For maximum flexibility, all three Star CBM Lectura administration modes are available: paper-only, online-only, and mixed, with the student using paper and the educator recording responses online.

Doris, Amy, and team have been tireless in supporting educators and students during this process. They’ve visited schools, provided professional development in Spanish, hosted Q&A sessions, and more. Educators’ feedback has been very positive, and we’ve made updates to the testing instructions and training materials based on what we’re learning. The field-testing data will also allow our psychometrics team to set the grade-level benchmarks and other norms that educators will see in the commercial version of the product.

Doris Chávez-Linville: Observing the field testing in person allows us to really connect with teachers and students as they’re using the assessment. I’m especially interested in observing the administration of the Passage Oral Reading measures (as modeled in this video). In the past, educators often relied on Spanish passages that had been translated from English—and usually not very well. As part of the design process for Star CBM Lectura, our internal team—whose members are former bilingual educators who also have assessment design experience—wrote passages in Spanish. We also sourced passages from Spain, Mexico, and Chile.

Like all of the content in Star, these passages have gone through a rigorous editorial process and content review to ensure they’re accessible and free of bias. There is another consideration, however. Spanish is the official language in 21 countries, which leads to a lot of variety. There are 11 different Spanish words for a drinking straw, for example. So we worked to balance this rich diversity in vocabulary with the need to ensure passages are accessible to all learners.

The response has been very positive. In one classroom, a student looked at the passage before her teacher had even asked her to read it. She immediately had a smile on her face and said, “This is real Spanish!” Students aren’t always excited about testing, but this was a genuine moment of joy in the classroom. When the language is authentic, students can feel it, because it’s part of their identity and their culture.

How might educators use Star CBM Lectura during the 2022–2023 school year?

Amy Patnoe: We intend to include 20 parallel forms of each measure. Because measures can be administered between screening windows, Star CBM Lectura not only screens but also provides real-time data on foundational literacy components in Spanish—data that many teachers have never had before. They can use this data to inform instructional design and Multi-Tiered Systems of Support. The data will also support conversations with colleagues (such as Related Service Professionals) and with students’ families and caregivers.

In my previous role, I was often invited to join Child Study meetings to help explain the nuances of literacy and language development in Spanish. I saw that the teachers of bilingual or multilingual students were being held to a standard and measure that was not designed for them, because they did not have access to authentic assessment tools. Watching these teachers as they tried to explain that their students were making progress—and that the assessment data did not paint an accurate picture—was heartbreaking.

Someone I admire once said, “Changing our beliefs begins with changing our language, with the words we use.” Star CBM Lectura provides educators with the understandings and concept knowledge of foundational literacy components in Spanish, and also with the data necessary to accurately understand the metacognition and literacy development of bilingual students. This is an assessment that schools and districts have needed for a long time.

Scott McConnell: Educators will also see continuity between Star CBM Lectura and our other Star Assessments, given the common design principles we’ve followed. This includes using authentic language, providing data that’s instructionally meaningful, making the assessment engaging for students, and ensuring that it’s both easy to use and psychometrically strong.

As Doris and Amy have explained, Star CBM Lectura helps us to deliver on our mission of accelerating learning for all children—not just some children. Respecting the language and culture that children bring to the classroom is an essential part of this work. Our approach at Renaissance is to keep the teacher and the student at the center, and to make sure that technology is there to help move learning forward. With Star CBM Lectura, we have a sensitive measure that shows how students are progressing toward becoming proficient readers in Spanish. This creates a really solid foundation for supporting biliteracy, whether we’re talking about Spanish-speaking students who are learning English, or English-speaking students who are learning Spanish in a bilingual program.

Doris Chávez-Linville: I always remind people that there is no such thing as a bilingual assessment. So instead educators use two monolingual assessments. The goal is for each one to be authentic to the language, and to truly assess the skills that are critical for reading proficiently. In English, this means Letter Names, as we’ve discussed. It also means onset and rime, which are often used as an indicator of kindergarten readiness.

Tools for assessing these skills have existed in English for many years. But teachers in the US have not had comparable tools in Spanish—where onset and rime do not exist, for example. So the ability to access an authentic, psychometrically solid tool in Spanish that can be used across schools and provides reliable data for decision-making is a game-changer, helping educators to more fully support literacy development in both languages. That has been our goal from the beginning, and I cannot wait for educators to start using this assessment.

If your school or district uses the Star 360 assessment suite, you now have access to Star CBM Lectura at no additional cost. If you’re not currently using the Star 360 suite, click the button below to learn more.