November 23, 2016

The challenge of a common definition

Though conversations about personalization and/or individualization abound, there remains shockingly little agreement on a definition. Many conversations take on a “kitchen sink” dynamic in which other approaches (e.g., mastery learning, universal design) are simultaneously discussed to the point of absolute confusion. With no clear definition and muddled conversations, substantive progress is severely limited.

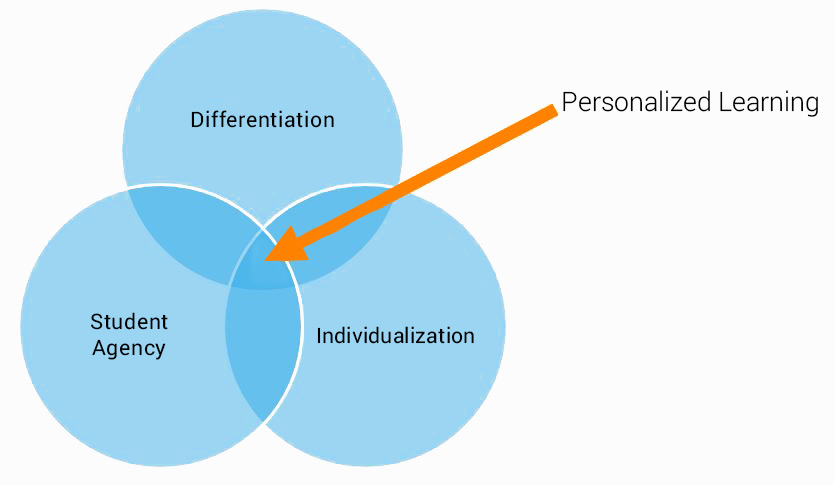

Personalization vs. individualization vs. differentiation

Educators intuitively understand that personalization, individualization, and differentiation are related. They acknowledge differentiation as a broader term and see personalization and individualization as more extreme forms of differentiation, yet they may have trouble distinguishing between the two.

A workable definition

To reconcile these semantic challenges, perhaps the most workable definition of personalized learning comes from the U.S. Department of Education (2016):

“Personalized learning refers to instruction in which the pace of learning and the instructional approach are optimized for the needs of each learner. Learning objectives, instructional approaches, and instructional content (and its sequencing) all may vary based on learner needs. In addition, learning activities are meaningful and relevant to learners, driven by their interests, and often self-initiated.” – U.S. Department of Education

This definition resolves the overlap of personalization, individualization, and differentiation in many conversations. Culatta (2016) extended this definition by suggesting that individualized learning refers to “learning experiences in which the pace of learning is adjusted to meet the needs of individual students, focusing on the ‘when’ of personalized learning,” while differentiated learning refers to “learning experiences in which the approach or method of learning is adjusted to meet the needs of individual students, focusing on the ‘how’ of personalized learning.” Personalized learning, then, envelops both differentiated and individualized learning, and it goes even further with the elements of student involvement and choice as noted in the definition above.

The essential three elements become:

- Differentiation—changing the instructional approach

- Individualization—changing the pace

- Student involvement—making students active participants in their own education

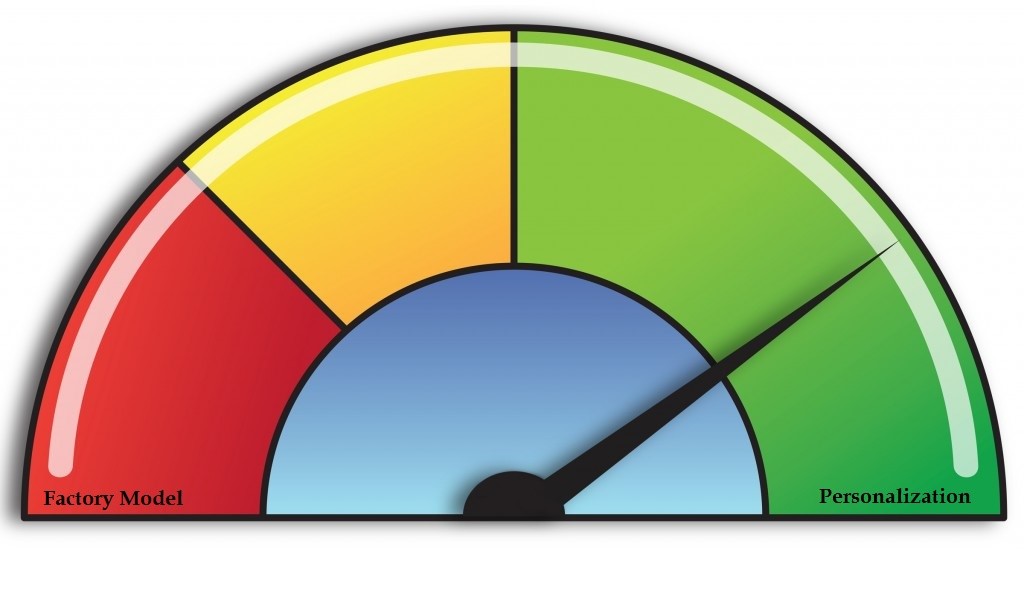

The result of this can be represented by the following continuum, where the traditional “factory model” is on one end, personalization is on the other, and in between are varying forms of differentiation or individualization:

How far does personalization go?

Both personalization and individualization imply looking at each student on a case-by-case basis, with some guidance around personalization referencing the crafting of “individual education plans for every student.” In such conversations, educators immediately become concerned about scale. How viable is it for a teacher who serves 150+ students to write, let alone follow, 150 different plans?

Generally, our profession has been far more comfortable with conversations of “differentiation,” and even in this arena, scale is a major concern. For example, Education Week posted a blog written by Jim Delisle titled “Differentiation Doesn’t Work.” This blog and a subsequent response from Carol Ann Tomlinson and rebuttal by Delisle were some of the most-clicked articles of 2015. If there’s angst about differentiation, imagine the undercurrents around personalization!

Ways to bring clarity

Working within this definition of personalization, some clarity may be achieved in the following ways:

1. View personalization as an end, not a means unto an end.

Discussions around and examples of personalization reference many other approaches, including competency-based learning, blended learning, inquiring learning, and others. Each of these instructional approaches could be undertaken by schools outside of any specific conversations about personalization. And personalization could be accomplished through all of these means and many more.

In all of this, if we view personalization as the ultimate goal—the end—we can view many others approaches as the means to achieve that end. Instead of focusing on personalization, which is ultimately too complex and varied overall to study directly, we need to look to the efficacy of the numerous approaches that might be used to personalize.

2. Acknowledge that personalization doesn’t completely mean what it means.

Despite the root word and references to/requirements of individual plans, many lauded examples of personalization also reference extensive group work on broad, multi-disciplinary projects and other cooperative activities. It is critical to understand that personalizing education certainly does not mean that everything is personalized at every moment.

3. Acknowledge scale and view personalization as a goal that will take years to achieve.

The scale of change that true personalization requires cannot be underestimated. Personalization is not merely a new pedagogical approach resulting in a slight or even moderate adaptation to daily practice; it is an attempt to fundamentally rework school as we know it.

As Rhode Island (2016) notes, “Attempts to personalize at a more granular level can quickly become burdensome—even for excellent teachers—in our industrial-age schooling model that was designed for efficiency not individuality.”

Personalization asks educators to envision operating in a world they cannot imagine because it is so very different from their reality. In seeking to lead personalization efforts, it is critical to position this goal as something that will take years to achieve. Taking steps to achieve personalization can then become a series of successive discussions on moving the needle. Based on where we now are, what strategy can we next implement to move the needle farther away from the factory model and closer to personalization?

4. Finally, is personalization really anything new?

It is, and it isn’t. Clearly, the scale personalization asks for is new. But, at the heart of it all, teachers’ efforts to respond to learners’ needs aren’t new at all.

Personalization can be viewed as the antithesis to the “factory model” of schooling; however, the factory model, in its purest sense, never existed. The moment a teacher first responded to a child’s question or needs, a dynamic unlike a factory was operationalized. Machines of mass production do not respond in any way to the irregularities or unique qualities of their raw materials, but teachers have always sought to humanize education. In this sense, personalization seeks to open up opportunities to humanize.

References

Culatta, R. (2016, March 21). What Are You Talking About?! The Need for Common Language around Personalized Learning. [Web blog post]. Retrieved from http://er.educause.edu/articles/2016/3/what-are-you-talking-about-the-need-for-common-language-around-personalized-learning.

Rhode Island (2016). RI Personalized Learning Initiative: An initiative to support personalized learning across Rhode Island.

Keep conversations flowing smoothly. Stay up-to-date on the most important assessment terms in education today with our free guide.