February 12, 2021

Each year, Renaissance’s What Kids Are Reading report lists the most popular books at every grade level, and also provides new insights into K–12 students’ reading habits. With the 2021 report arriving on March 2, we wanted to look back at the report’s history—and preview what’s new this year. We recently discussed these topics with Eric Stickney, our Senior Director of Educational Research; Heather Nagrocki, Senior Research Writer/Editor; and Amanda Beckler, Senior Research Analyst. Here are the highlights from our conversation, along with links to literacy resources.

Q: Why did Renaissance create What Kids Are Reading? What was the first report’s goal?

Eric Stickney: Bestseller lists and surveys of libraries can tell us which books are of interest to children and young people. But as Terry Paul, the co-founder and former CEO of Renaissance, liked to point out, our Accelerated Reader program shows us which books students are actually reading, not just buying or checking out. Because Accelerated Reader is used by millions of students across the US, we have a large national sample of which books kids are reading, along with data on their comprehension of those books and the characteristics of the books (word count, difficulty, etc.)

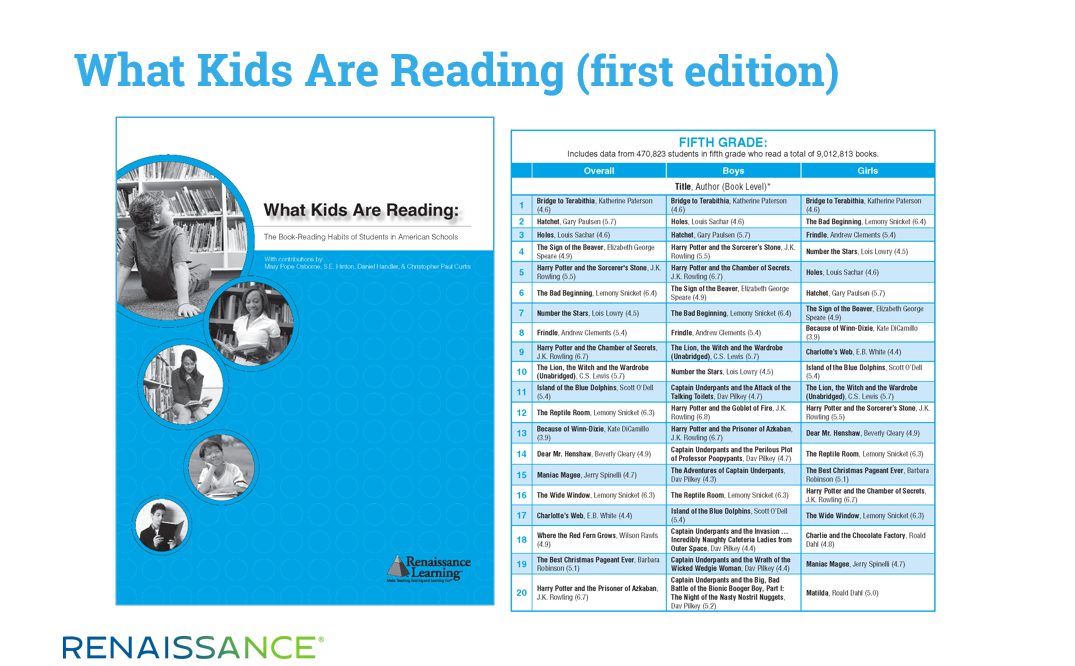

Terry realized that this data would be very useful to educators, librarians, parents—and even to the students themselves. His discussions with the Renaissance Research team led us to publish the first What Kids Are Reading report in 2008. It contained lists of the most commonly read books by grade and gender, along with statistics regarding how much reading students were doing at each grade level.

The report received a very positive response from educators and parents, and the media was interested as well. A story even landed on the front page of the Washington Post. That, in turn, sparked discussions with researchers, educators, and parents about whether students were reading sufficiently challenging books, or were doing enough reading period. Those are good discussions to have, and the positive response led us to commit to releasing new editions of the report each year.

Q: How has the report changed over the years?

Heather Nagrocki: The biggest change is the number of students included: from three million in the first edition to more than seven million this year. We’ve also made enhancements to the grade-level book lists. For example, we now flag nonfiction titles and titles that have Spanish-language quizzes available in Accelerated Reader. We’ve also started to combine book series into a single entry to allow as many unique books as possible to make it onto the lists. Books from several series, such as the Biscuit series, the Diary of a Wimpy Kid series, and the Harry Potter series, were dominating the lists in some grades. Listing the series as a single entry shows how popular the books are with students, while opening up space for additional titles that might otherwise get overlooked.

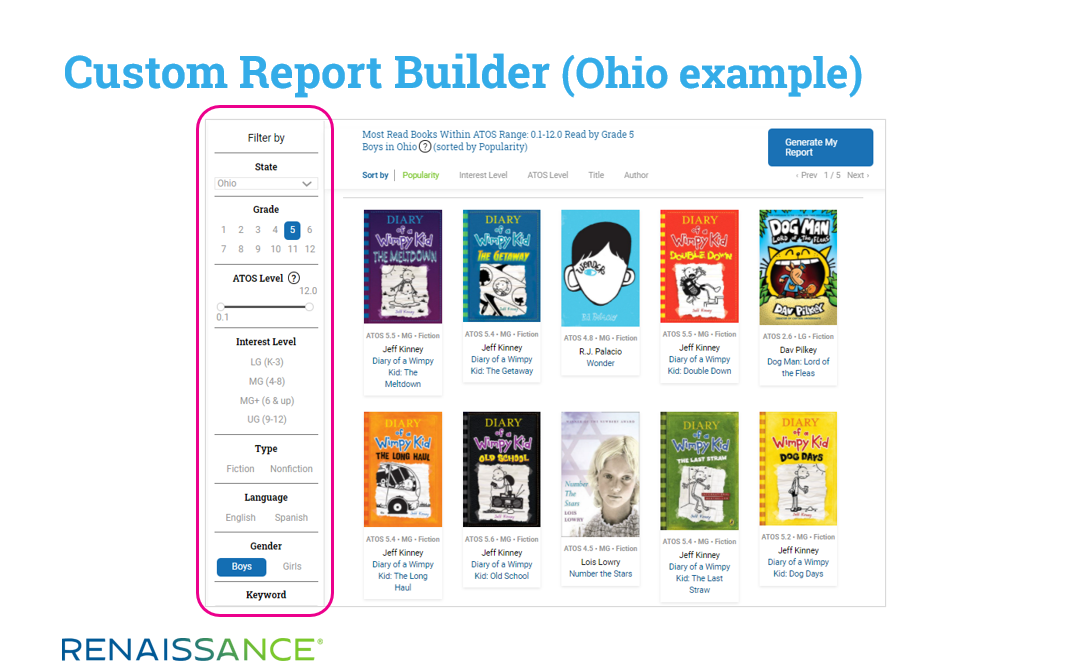

Eric Stickney: Another major enhancement was the launch of a companion website several years ago. In addition to downloading the formal report, educators, librarians, parents, and students can use the website’s Custom Report Builder to look at the What Kids Are Reading data however they’d like. For example, they can filter the results by state, grade level, reading level, gender, fiction vs. nonfiction, English vs. Spanish, and more.

A persistent challenge noted by educators and parents is that—beginning around grade 5—boys generally don’t read as much as girls, don’t read as well, and are more likely to be labeled as reluctant or resistant readers. One of the common issues is that they can’t find books that interest them. Using the Custom Report Builder, a grade 5 teacher in, say, Ohio could find the most popular books among fifth grade boys in that state. She could then share this list with the boys in her class, showing them the books their friends are reading.

Q: How has the process of creating the report changed since 2008?

Heather Nagrocki: We’ve become a lot more efficient at pulling the data, and we definitely have a list of “lessons learned” over the years. For example, for the first edition of the report, we pulled each author’s first name and last name to create the grade-level booklists. This worked fine in most cases…until we ended up with listings like “The Great Gatsby, by F. Fitzgerald.” We had to scramble to fix these entries before the deadline!

Amanda Beckler: As Heather mentioned earlier, the amount of data has also increased significantly. Starting in 2015, we began to include research analyses in the report, drawing on data from both Accelerated Reader and our Star Assessments. Using both sources allows us to tie the amount of time students spend reading to their reading growth, and to show the correlation between setting reading goals and student growth. We’ve also looked closely at nonfiction reading. In 2008, only 18 percent of students’ reading was nonfiction. Now, it’s 25–26 percent, reflecting the emphasis on informational text in many states’ learning standards.

The addition of myON to the Renaissance family gave us new insight into students’ digital reading habits, and the report now includes grade-level lists of popular digital titles as well. Analyzing students’ reading on myON also showed us something interesting about nonfiction reading. There’s a common perception that students prefer fiction to nonfiction, and it’s true that fiction makes up the bulk of students’ reading overall.

But when students have instant access to digital books on myON, the picture changes. As we pointed out in last year’s report, students in grades 3–8 spend more than 50 percent of their time on myON reading nonfiction titles:

This is what makes the process of creating the report so interesting each year: we’re never quite sure what we’ll find when we dig into the data.

Q: What other research questions has the report investigated? Which findings surprised you the most?

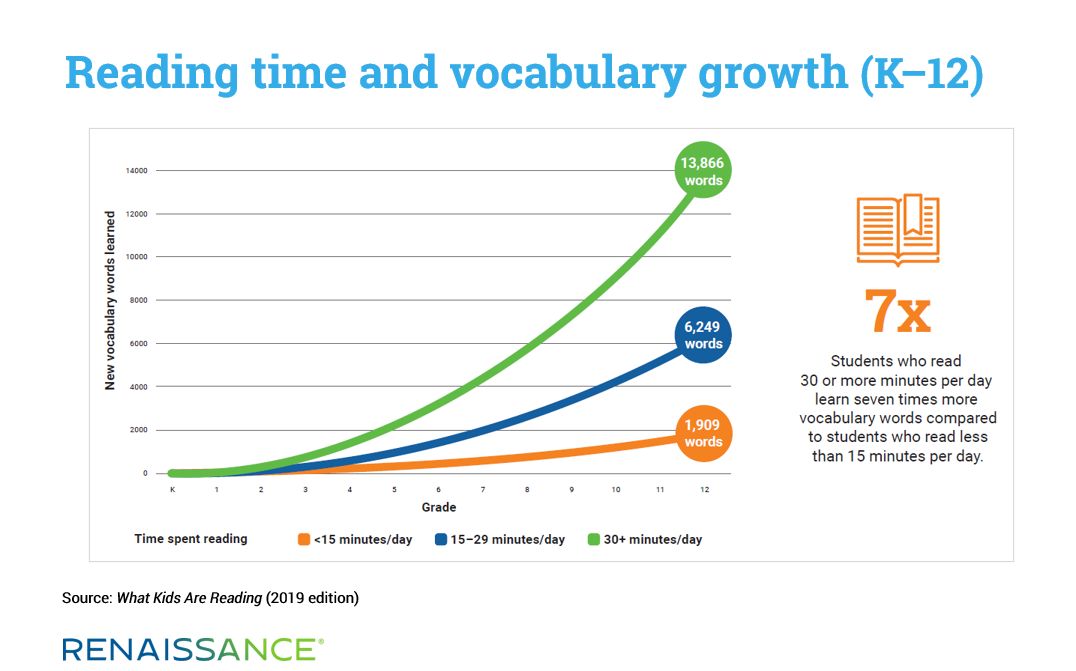

Eric Stickney: The analyses have definitely shown us the power of daily reading practice. Take vocabulary as an example. Reading researchers will tell you that exposing students to vocabulary in authentic text is critical for developing their background knowledge, their general reading ability, and their ability to tackle new, more challenging, and unfamiliar types of text in the future. In the 2019 report, we examined the impact of reading for just a few extra minutes per day on students’ vocabulary growth. It’s both surprising and heartening to see how dedicating a bit more time to daily reading practice results in significantly greater vocabulary gains across a student’s K–12 education:

We’ve also explored the relationship between the difficulty of what students read and what adults read. Some observers despair that kids don’t do a lot of reading “at their grade level” after they leave middle school. Our data shows there’s good news and bad news. Most high school students are choosing or being assigned books at a difficulty of around grades 6–8. That may sound concerning, but it turns out that we adults mostly read books at about that same level, if you analyze what’s on the bestseller lists.

So, there doesn’t seem to be a gap in terms of fiction reading. The larger concern is the nonfiction material, including both articles and books. There is a gap between the difficulty of the nonfiction books and articles high school seniors read and the text complexity they are expected to handle in college and career. On average, it looks to be about a three-year gap, because 12th graders are reading nonfiction books and articles mostly at a grade 7–9 level. However, the occupational, military, and college texts they will need to handle are typically around grades 10–14 in terms of text difficulty. So, there’s clearly more work to be done here.

Q: Each year, the report includes short essays by noted authors. Which essays are the most memorable?

Heather Nagrocki: There are too many to choose from! The Outsiders was one of my favorite books when I was growing up, and I approached S.E. Hinton to write an essay for the first edition of the report. I was so excited when she agreed!

Other authors who’ve contributed essays include Lois Lowry, author of The Giver; Christopher Paul Curtis, author of Bud, Not Buddy; Judith Viorst, author of Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day; Dav Pilkey, author of the Captain Underpants and Dogman series; Melba Pattillo Beals, a member of the Little Rock Nine, the first students to integrate all-white Central High School in Little Rock, AR, in 1957, and author of Warriors Don’t Cry; and Dr. Christine King Farris, author of March On!: The Day My Brother Martin Changed the World.

We’ve also had Donald Driver, the former Green Bay Packer and author of a series of children’s books about a boy named Quickie—a fun local tie-in for our Wisconsin-based company; Daniel Handler, author of the Lemony Snicket series; Jeannette Walls, author of the memoir The Glass Castle; and Ellen Hopkins, who’s written some memorable YA novels in verse.

For 2021, we’ll have essays by Jewell Parker Rhodes, author of Black Brother, Black Brother; Pam Muñoz Ryan, author of Esperanza Rising; Rob Harrell, author of Wink; and Yuyi Morales, author of Dreamers. Appropriately enough, each writer will reflect on how books and reading can help us all—kids and adults alike—to get through challenging times.

Q: What else can you tell us about the 2021 report? What will be new this year?

Heather Nagrocki: As always, the report will list the most popular books at each grade level—although this year, we’re providing side-by-side lists of the top 12 print titles and the top 12 digital titles. This reflects the major increase in myON usage we’ve seen over the last year, as educators and librarians have found new ways of getting books into kids’ hands.

For a few years, we’ve been highlighting titles that support social-emotional learning. For 2021, each grade level will feature a pair of books (one fiction, the other nonfiction) that address a SEL-related topic. We’re also highlighting five popular Spanish titles at each grade level, as well as books that promote diversity and inclusion. Finally, each grade will have a “New and Now” section, to highlight books published in 2019 or 2020 that students are just starting to discover.

Amanda Beckler: From a research perspective, we’ll be comparing students’ reading in fall 2020 to their reading in fall 2019. We’re obviously interested in whether students are reading more or less this school year. We’re also interested in the difficultly of the books they’re reading now, and how well they’re comprehending what they read.

2021 also marks the thirty-fifth anniversary of Accelerated Reader. In addition to the booklists and the research findings, we’ll profile several educators who are using AR to support distance and hybrid learning this year.

Eric Stickney: Beyond sharing data on student reading, the report’s goal has always been to celebrate books and to encourage students to read for pleasure, both in and out of school. We know from prior research that the characteristics of the reading that students do are strong predictors of how much they’ll grow achievement-wise, and the likelihood they’ll be able to understand more complex texts later in school, college, and career.

There is concern about how much students are reading, that video games and other distractions pull them away from books, and that the disruption caused by COVID-19 is having a negative impact on reading growth. So, while the 2021 report will offer new insights and information, its goal remains the same: to highlight popular and engaging books so that educators, librarians, and parents can help all students to find their next great read.

Learn more

Download the new 2021 edition of What Kids Are Reading now. Also, explore the new report’s most surprising insights in a free on-demand webinar.