June 5, 2014

Our brains thrive on repeated experiences. This explains why we seek to watch the same movies again and again and re-read favorite books. According to the health blog, “The Body Odd,” the drive to re-experience is a conscious effort to find deeper layers of significance in the material by revisiting it in the updated context of our own personal growth (Wolchover, 2012). In other words, as we watch a beloved movie many times, we ponder the images and story through a lens expanded by experiences encountered since the previous viewing. We may even recite dialog along with the actors. In doing so, the brain strengthens existing neural pathways, the film takes on new shades of meaning, and our understanding of it becomes richer.

It seems that this innate function of the brain—the conscious effort to find deeper layers of significance—is at the heart of what has become a potentially controversial concept; close, repeated reading as described in the Common Core State Standards. While some express concern that the CCSS focus on explicit meanings of text may devalue students’ personal experiences, others suggest that close repeated reading requires educators to bring readers and text close together through repeated, meaningful engagement with the text (Beers & Probst, 2013).

Regardless, the brain continues to crave close, repeated experiences with text. As we engage with the text through multiple readings and re-readings, the brain builds deeper layers of understanding about the text and our connection to it. What is intriguing here is that the distance between the reading and rereading need not be significant in terms of time. The distance need only to be separated by personal experiences that bring reader and text close. Educators understand the value of close work with texts such as strengthening reading fluency through reading practice, developing vocabulary, listening as texts are read aloud, reading with others, discussing the text with peers either in traditional face-to-face formats as well as an an eReading program, such as Subtext, that is built for reader engagement with text. Students using Subtext have multiple opportunities to interact closely with text.

While the Common Core State Standards have provided intense interest in close, repeated reading, the concept itself is not new, and it is not limited to reading. As a child, Abraham Lincoln would replay again and again the stories he heard his father tell until those repetitions brought him so close to his father’s stories that he could share them among his own circle of friends (Goodwin, 2005). Benjamin Franklin, in an effort to improve his own writing, repeatedly read noted essays to get so close to them that he could rewrite them in his own style (PBS, 2002).

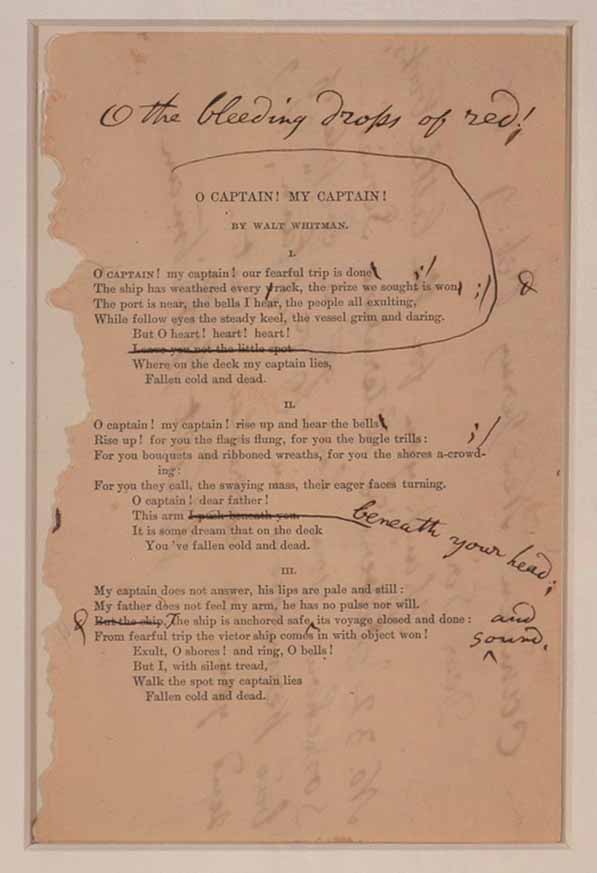

With Franklin and Lincoln in mind, get close to CCSS College and Career Readiness Anchor Standard 1 regarding close, repeated reading: Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions draw from the text. Read and re-read to get close to the opening phrase in Anchor Standard 1. Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly. Read it aloud. Read it to a colleague and ask how we lead students to arrive at what a text says explicitly. Experience close, repeated reading lesson exemplars, such as “The Gettysburg Address by Abraham Lincoln” found at http://achievethecore.org. Use this lesson as a guideline and lead students to an explicit understanding of Whitman’s poem O Captain! My Captain!

Bring the reader close by listening to a recitation of the poem. See suggested online sources below. Read along silently as you hear it recited again. Read the first stanza aloud with your colleagues, seek meaning through discussion. Read closely to determine what Whitman is saying—explicitly saying. Check out the YouTube clip from The Dead Poets Society where Whitman’s work is the unifying theme—see link below. Wonder how Whitman’s lines, first published in 1865, could have any connection to an American film first viewed 124 years later.

Continue; as your brain will crave more.

References

Beers, K. & Probst,R (2013). Notice & note: Strategies for close reading. Heinemann Press. Portsmouth, NH.

CCSS CCR Anchor Standard 1 http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/CCRA/R

Goodwin, D (2005). Team of rivals: The political genius of Abraham Lincoln. Simon &Schuster, New York, NY

Library of Congress O Captain! My Captain! http://www.loc.gov/teachers/lyrical/poems/my_captain.html

Library of Congress Oh Captain! My Captain! Image. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/images/tlc0405.jpg

Poetry Foundation. Whitman O Captain! My Captain! http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/174742

Public Broadcasting Service. Wit and Wisdom (2002). http://www.pbs.org/benfranklin/l3_wit_self.html

Student Achievement Partners (2012). The Gettysburg Address by Abraham Lincoln. http://www.achievethecore.org/content/upload/Grades_9-10_Gettysburg_Address_ATC.doc

Wolchover, N. (2012). Why books and movies are better the second time. http://www.nbcnews.com/health/why-books-movies-are-better-second-time-1C6436931?franchiseSlug=healthmain).

Whitman O Captain! My Captain! http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HSAymj4hp7Y

The Dead Poets Society http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qSjxkbe_Vr4

Curious to learn more? Explore the power of Renaissance Accelerated Reader.