May 14, 2015

My original post on teaching informational text through biography borrowed from the elements of art to engage students in new ways as they write about the lives of others. The post focused on three elements of art—form, texture, and line. In borrowing these elements, I introduced the concept of a biography as a “life portrait” (the literal translation of biography). For students writing a biography, the art element form refers to ways the student puts the information together, texture refers to the evidence cited, and line becomes the actual lines the student writes.

In the earlier post, we explored different forms for a life portrait; famous last words and a moment in time. This follow-up post, written in response to requests from readers and educators who have attended our onsite forums, presents four additional forms to explore with your students. As you work with these forms, keep in mind that it is the texture—the evidence—that gives the life portrait depth and invites the lingering look.

More “Life Portraits” Forms to Explore

A picture is worth a thousand words

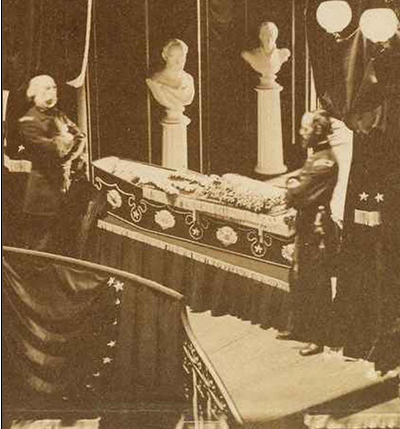

This life portrait begins with a photograph, for example, the photograph in the Renaissance Accelerated Reader 360® article, “Historian Will Donate Notes on Famous Lincoln Photo.” As students read the article, they learn about the 14-year old who found the photo and spent time researching it. Students writing life portraits with this form search for photographs of their subjects; then, just as the 14-year old did, they research the photograph and create a series of “photographer notes” related to it. For middle and high school students, this form lends itself to writing in real-world scenarios where one might be tasked to create a 1000-word description or explanation. (Writing a blog post comes to mind.)

Pocket anthology

This comes from a life portrait that explores the contents of Lincoln’s pockets at the time of his assassination. Why did he carry two pairs of reading glasses, what was up with the newspaper clippings, and did that Confederate five-dollar note tucked in his pocket seem out of place? As students research Lincoln, they find answers to these questions. You can view what was found in his pockets here.

With this form, students research any well-known figure to determine what he or she always carried. What caused the subject to keep that object (or those objects) close at all times?

Provided by Abraham Lincoln

Presidential Library & Museum

Abraham Lincoln lying in an open casket.

See you in the funny papers

This form is biography via political cartoons. Students research political cartoons about the subject of the biography. Once several cartoons are identified, students arrange them in chronological order. Then students research the context of each cartoon and develop a life portrait as a series of annotations about each cartoon. With this form, teachers would establish criteria for the annotation (for example, date the cartoon was published and context of the cartoon—what was going on in the culture at the time).

Dinner party

This one is more challenging to write, but it does open the door for creativity and deeper research. It also works well in collaborative life portraits. The biographer, or biography team, plans a dinner party for the subject. What will you serve and why? Will you serve indigenous foods? Did the subject have any unique dietary habits? Simply planning the menu requires students to present the basic data—birth date and place.

Once the menu is in place, the student works on venue. Would it be in a place significant to the subject’s childhood home, schools attended, or something in connection with the subject’s adult accomplishments?

Next comes the guest list. Who will be invited and why? For example, a student writing a biography of Julius Caesar would invite Brutus because, until his assassination, Caesar considered Brutus a son.* On the other hand, the guest list would not include Crassus, who might ruin dinner by arguing with Brutus about the Spartacan revolt. A good host or hostess is always prepared to start an engaging conversation, so this life portrait form should include “good conversation starters,” and why they are good, as well as “don’t go there” topics, and why these topics would create a most uncomfortable conversation at a dinner party.

Limitless Possibilities

Forms for life portraits are limited only by your imagination. Better yet, they are limited only by students’ imaginations. Accelerated Reader 360 provides access to intriguing articles that can serve as a springboard for a life portrait. These articles, in the hands of a skilled teacher, provide practice in the skills such as finding and citing evidence that lead students into the fine art of biography.

*“Et tu, Brute” is also a great “famous last words” life portrait form. In ancient Rome, a man would reserve this kind of informal, direct address for a son or other family member. In calling his attacker “Brutus,” Caesar acknowledged him as such and then submitted to the attack. Unless…Caesar never really uttered those words. The biographer would need to research to uncover the truth.