January 29, 2021

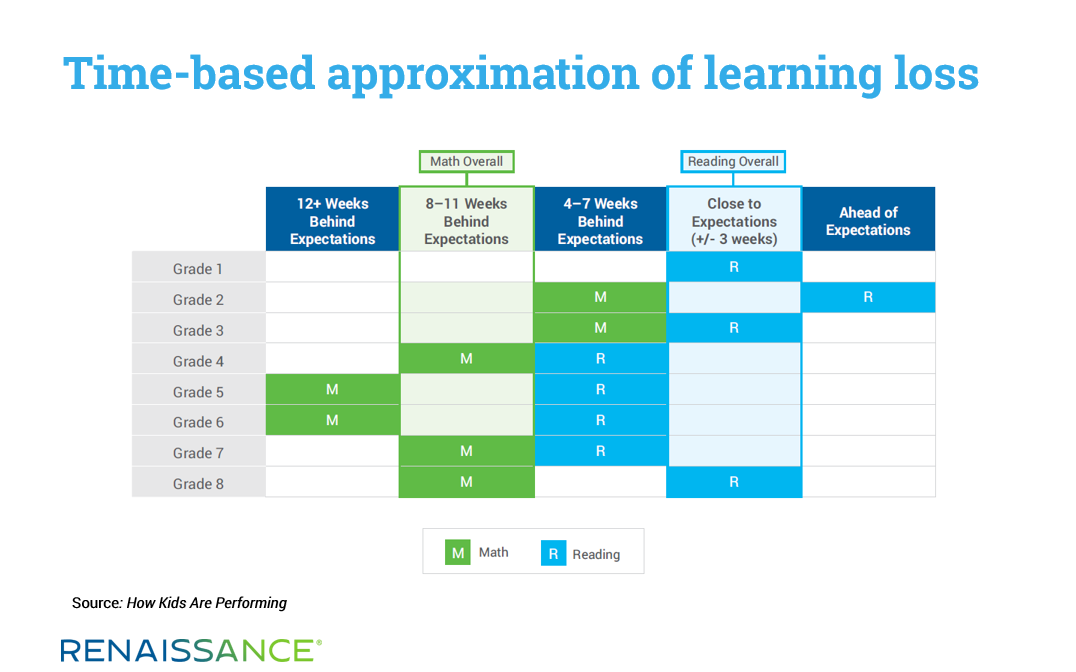

Last November, we released our How Kids Are Performing report, which uses data from five million student assessments to quantify the impact of COVID-related disruptions. While most students experienced modest declines in reading performance, math performance was impacted more significantly, with students in grades 4–6 showing the greatest declines.

This raises several questions for K–12 educators. Why was math impacted more than reading? How can we accelerate math growth this year, with so many students learning remotely? How can we use technology to support teaching and learning in mathematics—both inside and outside the classroom?

To help answer these questions, we recently spoke with Dr. Jan Bryan, National Education Officer at Renaissance; Jillian McDermott, a grade 4–5 teacher at Summit School of the Poconos in Pennsylvania; and Ryan Guerrero-Moreno, Product Specialist at Renaissance. Following are highlights from our conversation, along with links to helpful math resources.

Q: How much do we know about the COVID Slide in math?

Jan Bryan: As soon as school buildings closed last spring, we began hearing dire predictions about the scale of learning loss that students would experience due to COVID-19. But we weren’t able to truly quantify this until we had fall 2020 screening data, so we could compare students’ actual performance with where we’d expect them to be in a normal, “non-COVID” school year.

The How Kids Are Performing report shares our findings—specifically, that math was impacted more than reading at every grade level and across every demographic group. The following graph provides a stark indication of this, in the sense that the “worst” grades in reading (grades 4–7) are at the same level as the “best” grades in math (grades 2–3):

Q: Why was math affected more than reading? And why were middle-school students impacted the most?

Jan Bryan: There’s a common perception that everyone is willing to read with or read to children, but when it comes to solving math problems, it’s suddenly a case of “OK—see you later!”

On a more serious note, the writer Stephen Pinker describes math as “ruthlessly cumulative,” with each skill dependent on those that come before it. Because of the building closures last spring and the rush to implement distance learning, it’s not surprising that students missed instruction and practice on critical math skills, which then makes it difficult for them to progress.

Jillian McDermott: I wasn’t surprised to see that the middle grades have been impacted the most. In K–3, we’re teaching students the fundamentals of math—addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In grades 4–5, we add another level of complexity, such as decimals and fractions. Even before COVID, it was clear to me that students who hadn’t truly learned the foundational skills would struggle when they needed to apply and build on them in grades 4–5.

Q: How do you support students who need more work on foundational math skills?

Jillian McDermott: I’m lucky to work at a school that emphasizes project-based learning, and differentiation has always been central to my teaching. For math, I divide students into four groups, and the groups rotate through four stations. Group 1 works with me; Group 2 works on activities in our workbook; Group 3 completes online practice in Freckle Math; and Group 4 does hands-on activities and math games.

The groups are at slightly different levels, so when students are working with me, I focus on what they’re ready to cover next and where they’re encountering difficulties. Sometimes, there’s a clear need to review or reteach skills from earlier grade levels before moving on, or to explore different ways of solving a problem.

I use Freckle Math for just this reason. The adaptive practice component adjusts to each student’s level, and there are built-in supports—such as hints and short help videos—that keep students engaged when they might otherwise give up. Students who need practice on foundational skills get exactly this, and I can see in real time how they’re progressing.

Ryan Guerrero-Moreno: I’m always glad to hear about teachers who emphasize differentiation and who use Freckle to support this. By nature of a classroom, students are most often taught in groups, with limited 1:1 time. While this can be effective, we know that students are not homogenous and can really miss out on individualized skill-building in a classroom setting. Our focus on differentiation is related to why we are called “Freckle.” We often perceive freckles collectively, just as we perceive students collectively. The unique identity of an individual freckle can get lost or overlooked. The Freckle program constantly adapts to provide personalized practice, so the same phenomenon doesn’t occur with students.

Students receive a variety of question types (multiple choice, free response, drag-and-drop, etc.) when they’re working in Freckle. The program also provides students with regular reviews, particularly of concepts that proved challenging for them in the past, so they can develop the strong foundation Jillian mentioned earlier.

Q: How has COVID-19 impacted math teaching and learning?

Jillian McDermott: Every student in our school has a Chromebook, so technology was already embedded in our school day. When our building closed last spring, we only lost one day of instruction as we made the transition to remote learning. After that, we were back online, although most of the learning was asynchronous through the end of the school year.

This fall, we made the decision to remain fully remote, with live instruction four days per week. (Friday is for asynchronous learning activities.) I still have my four math stations, although these are now hosted in breakout rooms in our video conferencing system.

The teacher station has experienced the most change, because I’m no longer working with students face-to-face. I use Google Jamboard for this, which allows me to see students working on a problem, and allows them to collaborate with each other.

The Freckle station has probably changed the least, because my students were already familiar with using Freckle at home over the summer. The only “rule” I have is that they have to practice within the domain that we’re studying at the time. This was true in the classroom, and it still applies now that students are learning remotely.

Jan Bryan: There’s no shortage of research on effective strategies for helping students build positive math mindsets. Three that come to mind are frequent checks for understanding, deliberate practice to build expertise, and appropriate support and scaffolding. As Jillian and Ryan have pointed out, all three are built into the Freckle program, and students’ experience in Freckle is largely the same, whether they’re learning in the school building or at home.

Q: How has the COVID-19 Slide affected your students?

Jillian McDermott: The impact has been fairly minor in my classroom. As I mentioned earlier, my students use Freckle over the summer, and I’ve found that 10–15 minutes of daily practice can make a real difference. This was especially important last summer, and Freckle made it easy for me to see how much students were practicing, along with which skills they were practicing and how much progress they were making.

While my students have adapted to remote instruction, we’re moving through the curriculum more slowly than we would typically. We’ll likely cover all of the concepts by the year’s end, but I know I’ll have students using Freckle over the summer, to keep their skills sharp and to continue practicing new concepts.

Students obviously miss the hands-on activities we were able to do in the classroom. When we were working on fractions, for example, I’d give them a recipe for pancakes that served four people. I’d then ask them to quadruple this, to feed 16 people instead. Once they’d worked this out—and once I’d checked their calculations—they made the pancakes, right in the classroom. (Needless to say, I arranged for a few parents to come in and assist with this!)

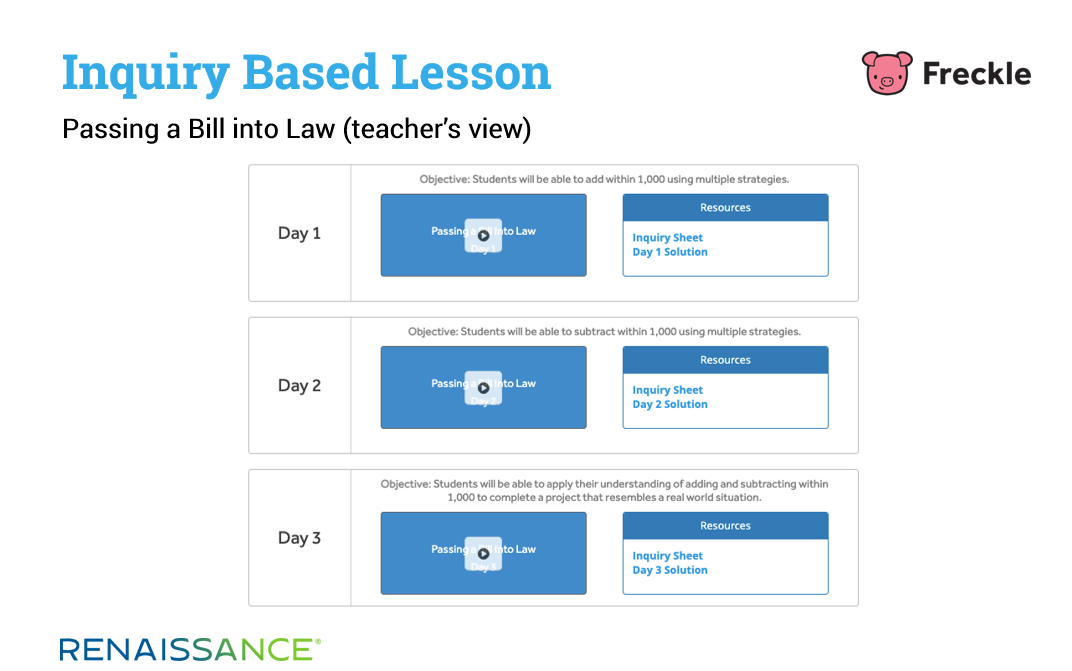

Freckle’s Inquiry Based Lessons support a similar real-world application of math concepts. When I taught grade 3, one of the students’ favorites was “Passing a Bill into Law.” This brings together math and social studies content, with students calculating how many votes a bill will need in the US Congress in order to pass. The activity is spread over several days, with students watching short videos and then calculating the number of votes that are still needed. Along the way, they discover that there’s more than one way to arrive at the correct answer, and they’re naturally curious about how their classmates solved the problem.

An activity like this is certainly do-able in a virtual environment, although it will require some coordination on the teacher’s part.

Ryan Guerrero-Moreno: Educators have been vocal about the challenges they face this year, particularly the need to make up lost ground while also covering grade-level content in a limited amount of time. We wanted to make sure that we support this need by enhancing Freckle Math to include Renaissance Focus Skills. Focus Skills give educators the ability to assign targeted practice on the most critical math skills at each grade level—the skills that students must learn in order to progress. We believe that Focus Skills are central to closing COVID-related learning gaps this year, and for maximizing the value of instructional time.

Q: What advice do you have around math motivation—especially in a distance learning environment?

Jan Bryan: Research shows that one key difference between students who achieve in math and those who don’t is mindset. I suspect we’ve all encountered students who say “I’m just not a math person,” as if they were destined from birth to either understand math or not. This always makes me think of Hamlet and the famous line “To be or not to be…”

The opposite of this is what I call the Jason Bourne approach. If you’ve seen the movies, you know that Bourne (who’s suffering from amnesia) discovers his identity step by step, relying on skills that he built through years of practice. Whether you’re teaching in-person or remotely, this is still the best approach. Students need to understand that skills build on each other; they need daily practice at the just-right level; they need opportunities to talk about math; and they need to regularly review skills so they’re ready to build on them in the future.

Each of these gives students greater agency in their learning, and we know that student agency is key to motivation.

Jillian McDermott: I couldn’t agree more. Growing up, I had some really inspiring teachers. I also had some who were very set in their ways. Looking back, I see how much I would have benefitted from learning more than one way of solving a math problem, and that’s why differentiation is so important to me. For example, some students find the box method really helpful for doing long division, while others don’t. That’s OK. It’s important for students to have multiple tools in their toolbox, and to be empowered to use the tools that make the most sense to them.

This is why I brought Freckle Math into my classroom back in 2017, and why the program continues to play such an important role. Rather than forcing students to work on the same thing at the same time and in the same way, Freckle gives students the independence to work at their level, and to build skills in the way that matches how they learn best. This is important every school year, but I think it’s critical now, as we work to support every one of our students during this pandemic.

Explore these resources for more insights on using Freckle to promote math engagement and student growth this year:

- Freckle Math Can Help Address Learning Loss (research brief)

- How Freckle Fits into Your Math Classroom (online resource)

- Trends in Student Outcome Measures: Freckle Math (research brief)

- Freckle at Home: A Guide for Families (online resource)

- Request a live Freckle Math demo