January 22, 2021

Over the last nine months, conversations about the scale of COVID-related learning loss have dominated K–12 education. These began last spring, when various predictions and projections about the “COVID-19 Slide” received widespread coverage, ranging from academic journals to the New York Times to CNN. Not surprisingly, the most dire statements received the most attention, with a tutoring center warning that “some children will never recover,” and one edtech vendor referring to today’s students as “the lost COVID generation.”

Now that we’ve analyzed students’ actual fall 2020 screening data, conversations about learning loss are far more interesting, timely, and relevant. As documented in the Fall Edition of our How Kids Are Performing report, things are not as dire as some had predicted. However, most students are unquestionably behind in mathematics, and we cannot afford any additional regression in reading over the course of the school year.

In instances like this, there is also a danger. We cannot afford to spend our time simply framing and admiring the problem. Without question, the months that students have spent away from school buildings has taken an academic toll. But what many people fail to understand is that even the most dire consequences of COVID-related learning loss are small when you consider the ranges and gaps in performance that already existed.

Understanding achievement gaps

I’m not the first commentator to make this point. Last June, Will Lorié of the National Center for Assessment noted that previously existing performance gaps “are greater than any differential ‘learning losses’ we will find between relatively advantaged and disadvantaged groups due to spring 2020 school disruptions.” This statement echoed a May 2020 EdWeek commentary by Heather Hill and Susanna Loeb, who stated that “even if the loss is on the larger side—say, the equivalent of three months—this change is small compared with typical existing learning differences among students as they enter a new grade.”

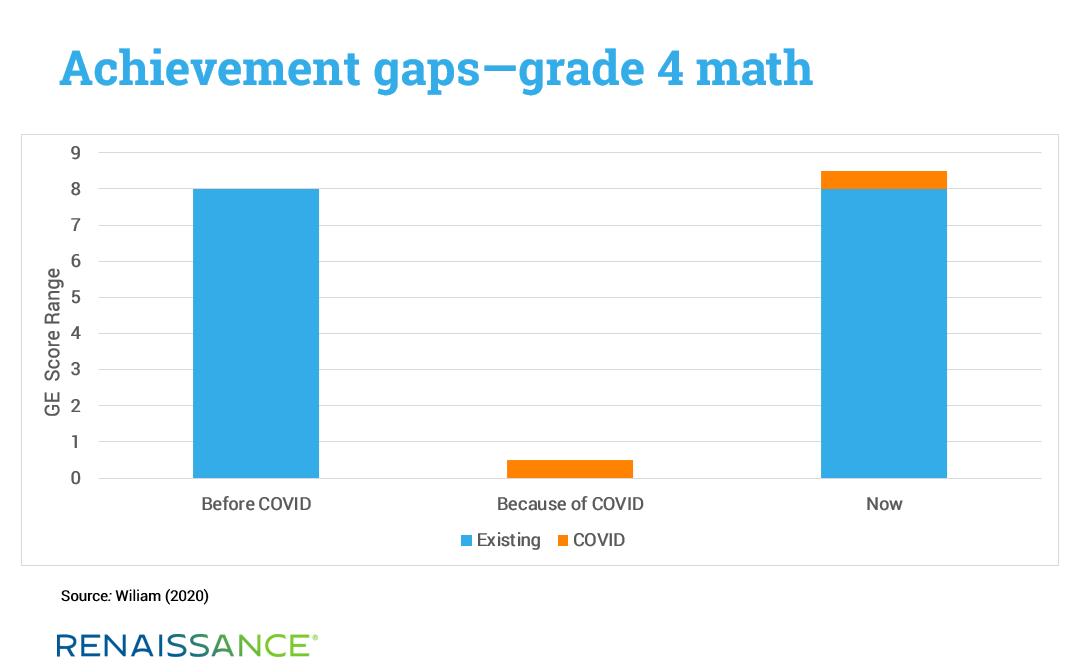

Dylan Wiliam (2020) used data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) to vividly illustrate this point. For example, the 2019 NAEP results for grade 4 mathematics show an average scale score of 242, with a standard deviation of 31 points. Wiliam applied these metrics “to estimate the number of students at each grade-equivalent level” within a nationally representative grade 4 classroom. This revealed that “there is at least an eight-year spread of achievement” in an average class of 4th graders—meaning “there were five students whose math achievement was no higher than the average 1st grader, and two students whose achievement would match that of the average 9th grader.” This range existed prior to COVID-19, and Wiliam estimates that the disruptions caused by the pandemic may, at most, have increased this eight-year range by another 0.5 years.

In an earlier study that focused on reading, Firmender, Reis, and Sweeny (2013) “examined the range of reading fluency and comprehension scores of 1,149 students in five diverse elementary schools, including a gifted and talented magnet school.” They “found a range in reading comprehension across all schools of 9.2 grade levels in grade 3, 11.3 in grade 4, and 11.6 in grade 5.” Taken together, these two models suggests that the average grade 4 math class would have students working at 8 different grade levels, while the average grade 4 ELA class would have a span of 11 grade levels—and this was before the pandemic.

Putting COVID-19 in perspective

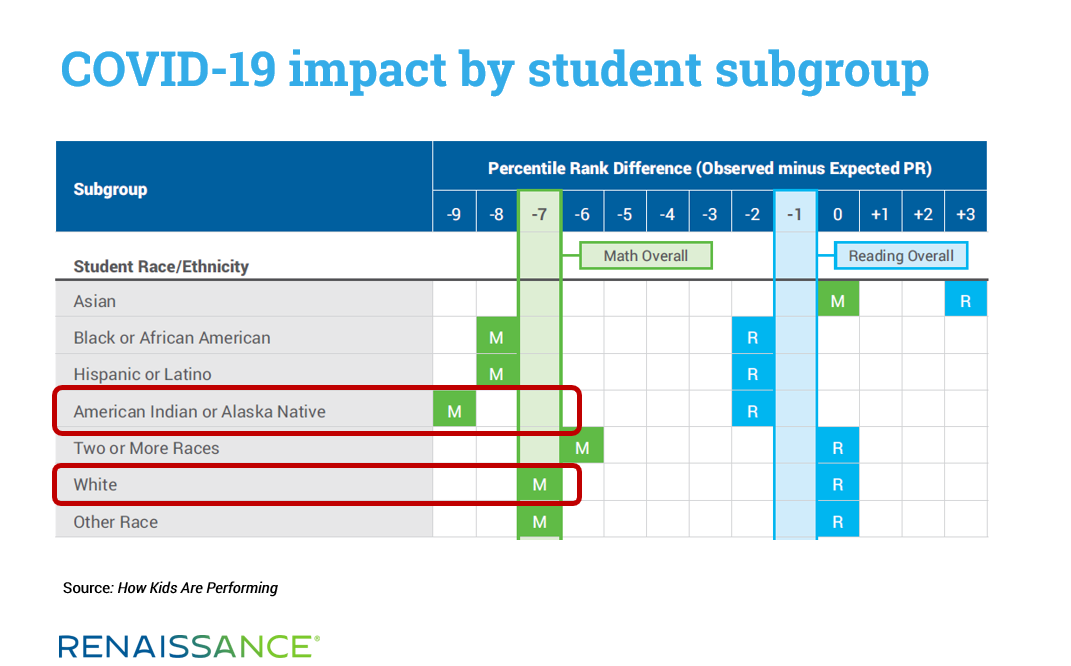

Understanding the larger perspective around achievement gaps helps us to make sense of two findings in the Fall Edition of How Kids Are Performing that may initially seem to contradict one another. In section 3 of the report, we document that some student subgroups have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. For example, we see that American Indian and Alaska Native students have experienced a 9-point drop in mean percentile rank scores in math, while white students have only dropped by 7 points.

Immediately after this, we explore the question of whether existing achievement gaps were exacerbated, and we present findings that seem to contradict those above. The report explains that “to determine whether achievement gaps are now larger due to the pandemic, we examined differences between student groups as a function of both race/ethnicity and prior achievement.”

In the first analysis, looking at differences among ethnic groups, we found that “there was no consistent or clear trend.” There were instances where gaps widened slightly and others where these gaps shrank, “suggesting that the pandemic has not yet exacerbated existing achievement gaps by race/ethnicity.”

The second analysis involved looking at differences in performance in consideration of prior achievement. For this, “we categorized each student in our matched sample as performing at a Low (Percentile Rank 1–34), Typical (PR 35–65) or High (PR 66–99) level, based on their pre-pandemic normative performance.” We found that “the pandemic’s impact appears to be approximately equivalent across lower, typical, and higher achieving students.” This means that the pandemic “has not led students with relatively low pre-pandemic normative performance to fall further behind their relatively higher performing academic peers,” given that higher-performing students experienced similar relative drops in performance. Everyone dropped fairly equally, resulting in lowered overall performance, but not in wider achievement gaps.

In some sense, these two findings raise questions. How can some demographic groups show larger drops than others—and yet gaps not be exacerbated? This is primarily a matter of scale. Experiencing a drop of 1–2 additional percentile ranks isn’t definitively significant when we acknowledge the much larger scale of the gaps that already existed. In essence, the COVID-19 Slide is, so far, a comparatively small addition to a much larger problem. To overly focus on the short-term loss related to COVID-19 is a perfect example of “not seeing the forest for the trees.” Many commentators have, in fact, been focusing on the COVID-19 “tree” without perceiving the performance gap “forest” that is the real challenge before us.

Just to be clear: I am not contending that COVID-related learning loss is irrelevant. To be sure, the disruption to schooling last spring has made a bad situation worse. I am, however, contending that our focus needs to be on the larger picture of gaps in student achievement, lest we fail to understand the landscape we are negotiating.

Sadly, many students are not only lost in the achievement gap forest, they are becoming more and more lost as time goes on. More than 15 years ago, Françoys Gagné (2005) analyzed data from the Iowa Test of Basic Skills and found the shocking reality that “the achievement gap widens by about 250% between grades 1 and 9.” Even before COVID-19, our educational system was not only failing to close gaps, but was actually making them worse. In a medical setting, this would be similar to a patient receiving continuous treatment and getting consistently worse. We must think deeply about what this means and what reforms we need to make in order to serve our students more equitably, both now and in the years ahead.

“Education reform is learning recovery”

Calls for reforming K–12 education are clearly not new. As Lorié (2020) notes, “Since the 1960s, schools have been called to close inter-group gaps in academic achievement measures.” He adds that while “learning loss” is a relatively new term, everything about “education reform is learning recovery.” So, what types of educational reform will educators need to undertake in 2021 and beyond?

The COVID-19 disruptions provide a critical opportunity to re-think our previous assumptions and practices. As Lorié notes, “If we are to do the work of learning recovery, let us take advantage of this moment to recover not only from the losses of one season but also from those that have been with us for decades.”

At Renaissance, we can provide you with tools and insights to support this important work. Our Focus Skills help you target the building blocks of learning at every grade level—the skills that students must master in order to progress in reading and mathematics. Star Assessments provide actionable formative and interim data so you can better understand each student’s achievement, growth, and instructional needs. And Schoolzilla greatly expands your reporting capabilities, so you can easily disaggregate data by student subgroup to identify equity issues and direct resources where they’re needed the most.

Change is never easy, and I don’t want to minimize the challenge that lies before us. But, in my experience, K–12 educators never lack for new ideas, and are willing to do whatever it takes to help students succeed.

References

Firmender, J., Reis, S., & Sweeny, S. (2013). Reading comprehension and fluency levels ranges across diverse classrooms: The need for differentiated reading instruction and content. Gifted Child Quarterly, 57(1), 3–14.

Gagné, F. (2005). From noncompetence to exceptional talent: Exploring the range of academic achievement within and between grade levels. Gifted Child Quarterly, 49(2), 139–153.

Hill, H., and Loeb, S. (2020). How to contend with pandemic learning loss. Retrieved from: https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion-how-to-contend-with-pandemic-learning-loss/2020/05

Lorié, W. (2020). Contextualizing COVID-19 learning loss and learning recovery. Retrieved from: https://www.nciea.org/blog/school-disruption/contextualizing-covid-19-learning-loss-and-learning-recovery

Wiliam, D. (2020). COVID-19 learning loss: What we know and how to move forward. Retrieved from: http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/rick_hess_straight_up/2020/08/covid-19_learning_loss_what_we_know_and_how_to_move_forward.html

Learn more

Watch our recent webinar for more insights on the COVID-19 Slide, learning recovery, and educational equity this school year. To access the webinar, click the button below.